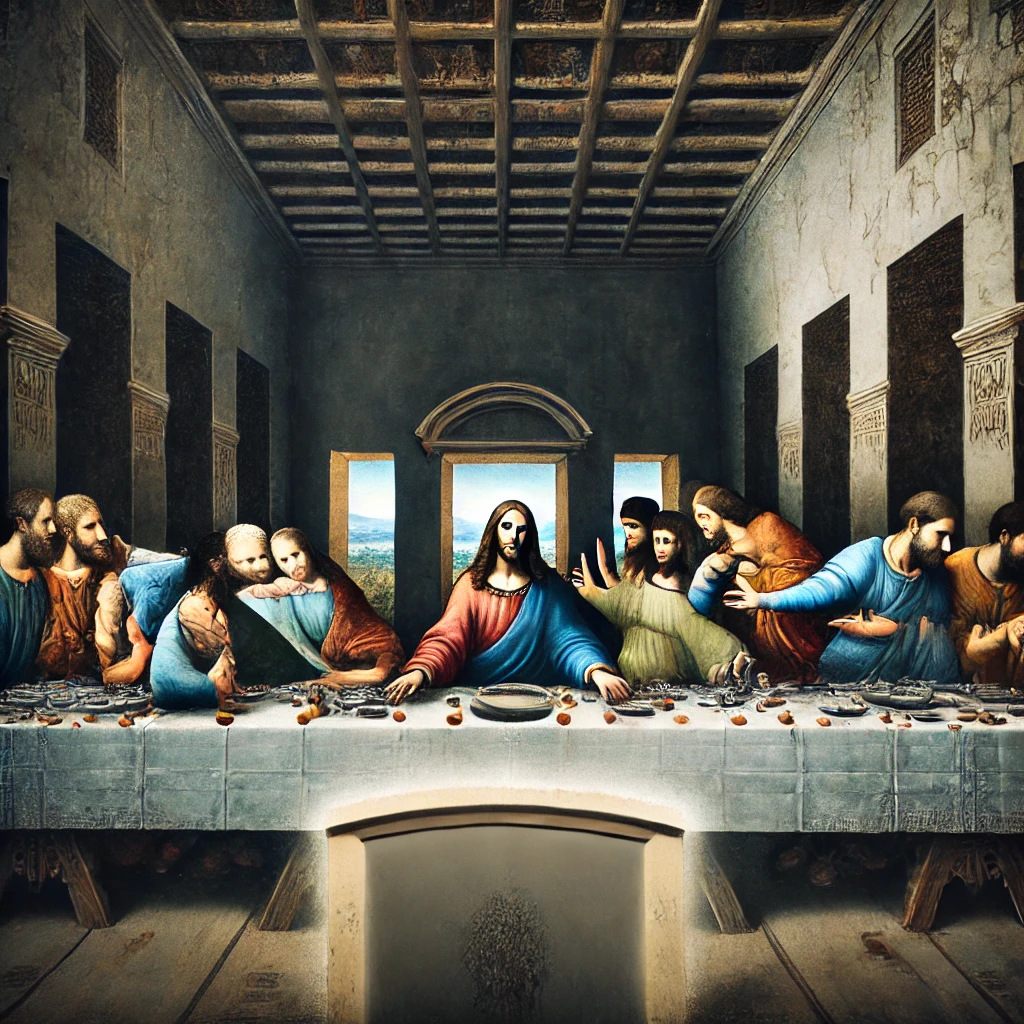

Leonardo da Vinci’s masterpiece, The Last Supper, depicts the prophesied betrayal of Jesus and remains a masterpiece of historical and artistic value to this day, thanks to da Vinci’s experimental techniques and the subsequent destruction and restoration of the work.

“One of you will betray me.” (John 13:21)

We’ve all heard this phrase before, a prophecy made by Jesus during his last meal with his disciples on the eve of his crucifixion. It’s more than just a historical statement; it touches on themes of human betrayal, atonement, and divine foreknowledge. The prophecy was a prelude to the huge theological event of Jesus’ death and resurrection, and its impact was not limited to religious doctrine. The scene has since inspired countless artists and has become a central theme in Christian art.

There is a great work that vividly depicts the 12 disciples, each with his or her own personality, as they react to the prophecy of their master’s death. This is Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper (La Cène). Through this scene, da Vinci sought to visually convey the tension and tragedy of the moment by expressing the personalities and emotions of each of the disciples. His work is not just a religious painting, but a masterpiece that explores the human psyche and its complexities.

The Last Supper, created over two years at the end of the 15th century, is still appreciated more than 500 years later, but it has been repeatedly damaged and restored over the centuries due to inadequate painting and unforeseen and unfortunate events during its production. At the time, the Renaissance was revitalizing the fresco technique of painting on wet plaster walls with water-soaked pigments. The paintings soaked into the walls and were virtually indestructible once they dried. This had the advantage of making the mural and the architecture one, allowing it to stay that way for a long time. However, the technique was more than just technical, it was also challenging, requiring the artist to work quickly and accurately.

The downside was that the painting had to be completed quickly, before the plaster dried, and it was nearly impossible to retouch. Da Vinci used somewhat experimental techniques to compensate for these problems, and as a result, the masterpiece suffered from mold before it was even finished, and pigment ran out as soon as it was finished. Da Vinci’s choices ultimately posed a lasting threat to his work, and its preservation and restoration remains a major challenge for future generations.

So what was the new technique?

The Latin word ‘temperare’, which means ‘to mix, to blend’, is a type of paint made by mixing pigments from colored minerals or plants with egg yolk, glue, honey, fig juice, etc. Used since the 6th century BC or earlier, tempera is the oldest known painting material in Italian history and can be found on the coffins of ancient Egyptian mummies as well as in Korean murals. Throughout antiquity and the Middle Ages, tempera was used in many different regions, especially for religious subjects and portraits. Unlike the fresco technique, which is a wet method that is painted quickly before the wall dries, tempera follows the secco technique, which is a dry method that is painted on dry walls or wooden boards. As a result, the pigment runs off faster and lasts less time than frescoes, which are integral to the wall. However, it was a favorite of Italian painters during the Renaissance because of its superior color rendition compared to frescoes, and the fact that brushstrokes remain clear, allowing for fine detail.

Da Vinci used oil tempera mixed with tempera to create his paintings over time, and he painted without applying wet plaster. This was a mistake due to his lack of experience with tempera murals. The walls of the monastery’s refectory were damp, and in such a humid environment, he had to use the fresco technique, not the secco technique. The pigments, which were not properly absorbed into the plaster, immediately began to flake off. In addition, the painting was damaged beyond recognition after two major floods and the bombing of the monastery during World War II. A major restoration was carried out over the next 20 years, from 1979 to 1999, but much of the work was already so badly damaged that it was not possible to restore it precisely. The difficulty of conserving the work, which has tarnished da Vinci’s reputation, has reminded many of the importance of choosing painting techniques.

Tempera, which was introduced to Europe in the early 13th century, reached its peak during the Renaissance in the 15th century. Until oil painting took over at the end of the 15th century, tempera was primarily used to paint murals in medieval churches or cathedral refectories. Painters of the time who used tempera include Berlingieri, Raphael, Leonardo da Vinci, and Duccio. However, in the mid-15th century, the Dutch painters Jan van Eyck and his brother, Jan van Eyck, mixed egg yolks with Bruges white varnish, a type of turpentine, to improve upon the disadvantage of tempera, which dried too quickly, and the paint became transparent and detailed, unlike the opaque secco and less detailed frescoes. This technique was later developed further and used by European painters in the Baroque period under the name of oil painting. Oil paintings allowed for playfulness and a wide range of textures, and the consistency of the varnish controlled the speed of drying and the presence or absence of gloss. Because of these advantages, tempera was neglected for a while, but in modern times it has been used by some painters who are looking for an individualized touch.

Tempera is a painting tool with a long history, having been used by countless painters since B.C. Throughout its history, it has evolved through various experimental attempts to improve its shortcomings, making it the ancestor of today’s oil painting. The value of tempera works is still recognized today, and it will continue to have a place in art history as well as contemporary art. Da Vinci’s The Last Supper is much more than just a painting, and in addition to its artistic value, it remains highly influential in its religious and historical context. In this sense, it remains a timeless masterpiece and will continue to inspire and teach people for many years to come.