Satoshi Kon’s Perfect Blue explores the identity confusion and psychological struggles of Mima, the main character, as she transitions from idol to actress. The movie explores the complexity of identity by skillfully blurring the lines between reality and fantasy, creating endless confusion for the viewer, and showing how Mima loses herself in her quest to find her true self.

I was impressed by Satoshi Kon’s work, and I was drawn to the dreamy atmosphere, colors, and darkness of his compositions. His works often leave a lasting impression on the viewer with their unique blend of reality and unreality. I’ve always wondered what he wants to say through his films, and I chose to take this opportunity to explore it in more depth. I chose Satoshi Kon’s Perfect Blue because it is his debut feature-length animated film for theaters. I was curious to see how his color palette emerges in his first feature and how it connects to his later work. I was especially intrigued by Perfect Blue because of its famous homage to Darren Aronofsky and the controversy over its plagiarism from his film Black Swan. I wanted to see for myself why this film is considered more than just an animation, but a psychological thriller and a work that can be analyzed semiotically.

It’s hard to single out any one scene, but I was impressed by the various devices used to confuse the audience by shifting between dreams, reality, and theater. Satoshi Kon maximizes the suspense by trapping the audience in a room of mirrors, blurring the lines between what is real and what is illusion. He uses devices such as tapping the shoulder with his hand to bring you back to reality like a bubblegum popping, and the repeated use of the line “Who are you?” to drive the audience deeper and deeper into confusion. These devices are constantly present throughout the movie, leaving the audience to piece together the pieces of the puzzle themselves. The chase between Rumi and Mima in the latter half of the movie felt like the culmination of that confusion. It’s creepy to see Rumi, as Mima, reach out and bask in the lights of the oncoming truck as if they were spotlights on a stage. This scene completely blurs the line between reality and fantasy, and conveys a sense of confusion to the audience. While some of the scenes were graphic and disturbing, they were used as a tool to further highlight the confusion and confusion of identity that the film was trying to convey. In the end, we are left with questions like, did Mima really kill her? Who killed her? Is she really dead?” I think the movie did a good job of creating a confusing situation that kept me on the edge of my seat until the end.

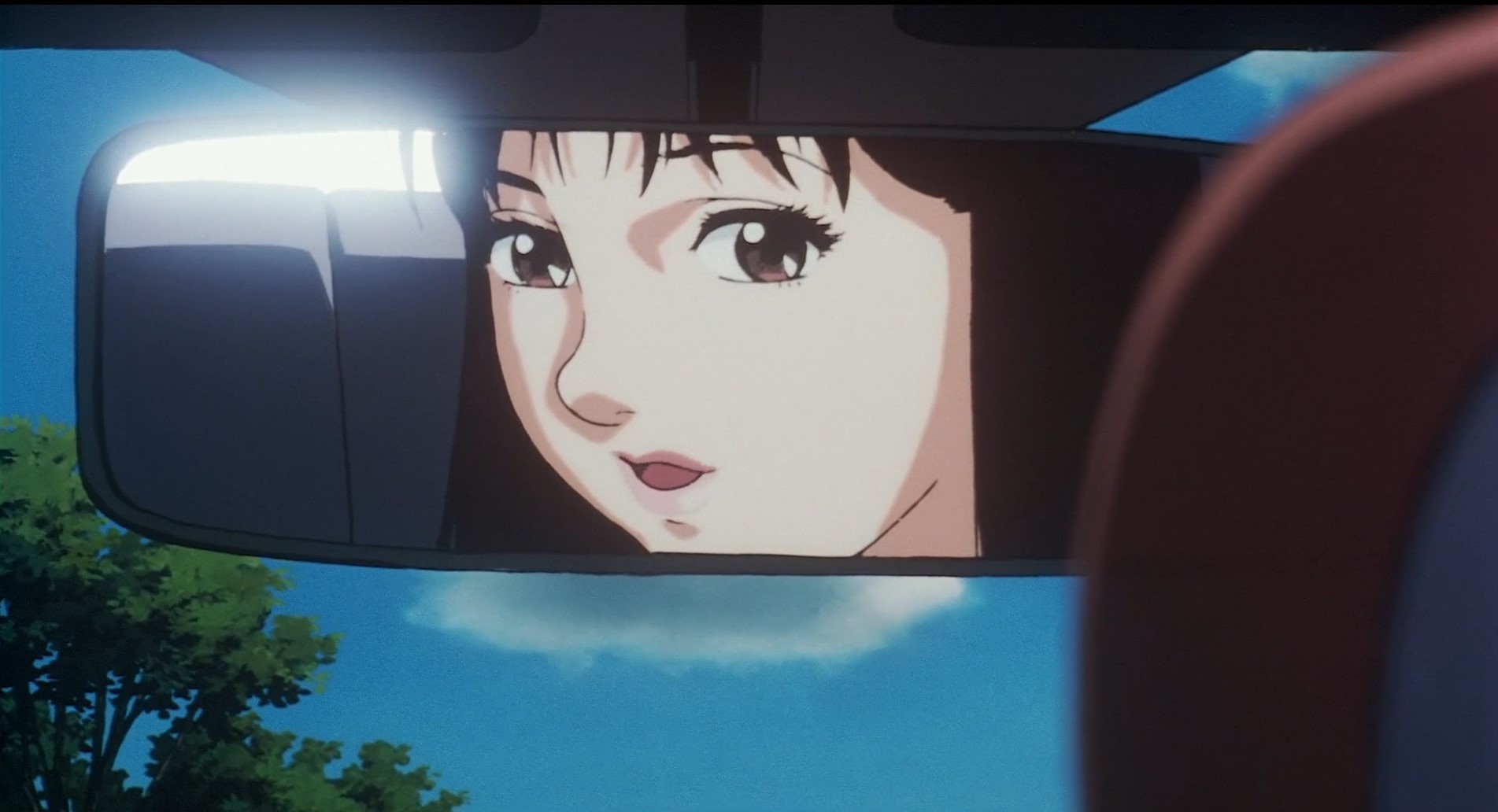

The main character, Mima, lives her life as an idol singer, but she realizes that her popularity will not last long and chooses to become an actress at the advice of her agent. Her manager, Rumi, a former idol singer herself, strongly disapproves, but Mima decides to take on a new challenge. She is cast in a psychological thriller drama called Double Bind and makes a bold choice to establish herself as an actress. Her actions, such as filming herself being raped and posing nude, make a huge difference to her image, but they also cause deep turmoil within her. Then, she discovers that someone is monitoring her every move on a site called “Mima’s Room,” which was mentioned in a letter she received on the day she retired as an idol. As Mima loses herself more and more, she becomes confused about her identity and her relationships with the people around her, and her confusion is compounded by the mysterious events that occur around her. A letter addressed to her explodes, the PD of the agency that pushed her to become an actress is injured, and the writer and photographer of the drama she stars in are murdered. Despite this, Mima has dreams of killing them, and when she eventually finds bloodstained clothes in her closet, she fears that she may be the culprit. Later, Mima is kidnapped by Uchida, who has been stalking her, but manages to escape. However, it turns out that it was all the work of Rumi, who has been pretending to be Mima, running Mima’s Room and imitating her. Rumi desperately chases after Mima, but in the midst of her frantic chase, she sees a truck coming and welcomes it with open arms as if it were a stage light. Rumi ends up in a mental institution, where she lives as the idols Mima and Rumi, until years later, when Mima visits her in the hospital, she looks in the rearview mirror of her car and says, “I am the real Mima.”

This work can be interpreted in terms of Roland Barthes’ concept of a “healthy” sign. A healthy sign is one that never passes itself off as natural in order to draw attention to its own arbitrariness, but rather signals its relative and artificial position even at the very moment it conveys meaning. Numerous devices in the movie act as these ‘healthy’ signs, constantly reminding the audience that ‘this is a movie’. For example, the countdown in the middle of the movie, the crew jumping out of nowhere to clap, and the repetition of the same scenes are constant reminders that this is not just a story, but a fiction created in the medium of film. However, the presence of these live-action cinematic tools in the animation makes it feel more theatrical and artificial, which in turn emphasizes the arbitrariness of the symbols. The film is made up of realistic and representational drawings, or symbols, but it confuses the audience by making them realize that these symbols are sometimes neither realistic nor representational. The arbitrariness of these symbols is also reflected in the appearance of Rumi, the manager, in the form of Mima, the protagonist, and the audience is forced to constantly think about the meaning of the symbols. This structure is also repeated in the film’s narrative structure, which remains in the viewer’s mind even after the movie ends, inviting endless interpretations.

The point where I felt moved and connected with this film was watching how various characters intertwined around the character of Mima through their different obsessions and desires, including Mima, who dreamed of becoming a singer but compromised with reality and pursued the path of an actress; Uchida, who pathologically chased after Mima, a fictional idol she created; and Rumi, who sought vicarious satisfaction by projecting her unfulfilled dreams onto Mima, and thought deeply about what the true form of ‘me’ is. In the movie, Mima loses her identity and gradually becomes confused and unsure of who she is. I’m sure I’m seen by many different people, and there are many people who remember me differently from the person I know. This perspective made me think about being in charge of who I am. Throughout our lives, we choose one of the many ways we are seen by others and believe that we are who we are. But is there really a “me”? Or are there just different shapes of me? The scene in which Mima says, “This is the real me,” at the end of the movie expresses this concern. But the question remains, what is that real “me” and is it even possible to find that true self?

I’ve heard that the director regretted not being able to include enough scenes involving fish due to budgetary concerns, but I’d like to delve deeper into the meaning of Mima’s “fish.” Fish often symbolize dreams and the unconscious, and I wonder how they relate to Mima’s psychological state in this film. I’m also intrigued by the symbolism of the awl, a weapon that appears repeatedly in the movie. The awl is sharp and pointed, and can be interpreted as a tool to pierce through something and reveal the truth, a symbol that plays an important role in Mima’s process of facing her own pressures and the truth. Comparisons with Darren Aronofsky’s Requiem and Black Swan could also be an interesting topic of study. Both of these films depict the protagonist gradually crumbling under the pressure of reality and inner conflict. It would be interesting to analyze their similarities and differences with Perfect Blue.

Finally, it’s worth thinking about the meaning of the title Perfect Blue. It literally means “perfect blue”, but “blue” can also mean melancholy. So does it mean “perfectly depressed”? It’s unclear how this title relates to Mima’s identity confusion, and why it’s called “perfect blue” when the story is about her finding herself in the end. Mima seems to have found herself at the end, but is she completely healed of the confusion and hurt she experienced along the way? Or is she just trapped in another illusion? The film leaves many questions unanswered, even after writing this report. As such, Perfect Blue is not a movie that you can simply watch once and be done with it, but rather one that keeps you thinking and leaves room for interpretation. Because of this complex appeal, I find myself wanting to watch it again.