The Act of Killing examines the 1965 Indonesian coup d’état from the perspective of the perpetrators, who are hailed as heroes for the massacres they led in the name of anti-communism. The film sharply exposes the violence of social structures and power, and asks what lessons we can learn from it.

During the 1965 coup in Indonesia, the military secretly killed more than one million communists, intellectuals, and Chinese in the name of “anti-communism. This tragedy was a state-sponsored, organized genocide that left an indelible scar on Indonesia’s modern history. Now, 40 years later, the mastermind of the massacre, Anwar Congo, has been hailed as a national hero and lives a life of luxury. Anwar Congo was once just a neighborhood thug, but by killing and terrorizing people in the name of anti-communism, he became a powerful figure in Indonesian society. This rise to power is not just an individual success story, but a reflection of the structural problems of the country and society as a whole, revealing a grim cross-section of Indonesian society.

Despite the fact that they know that killing is wrong, they try to justify and rationalize their actions. Rather, they use killing to demonstrate their power and ability. These attitudes are more than just self-justification; they are indicative of a pervasive culture of violence and oppression in society. In this process, a distorted social structure is formed in which the heinous act of murder is taken for granted and even justified to gain power.

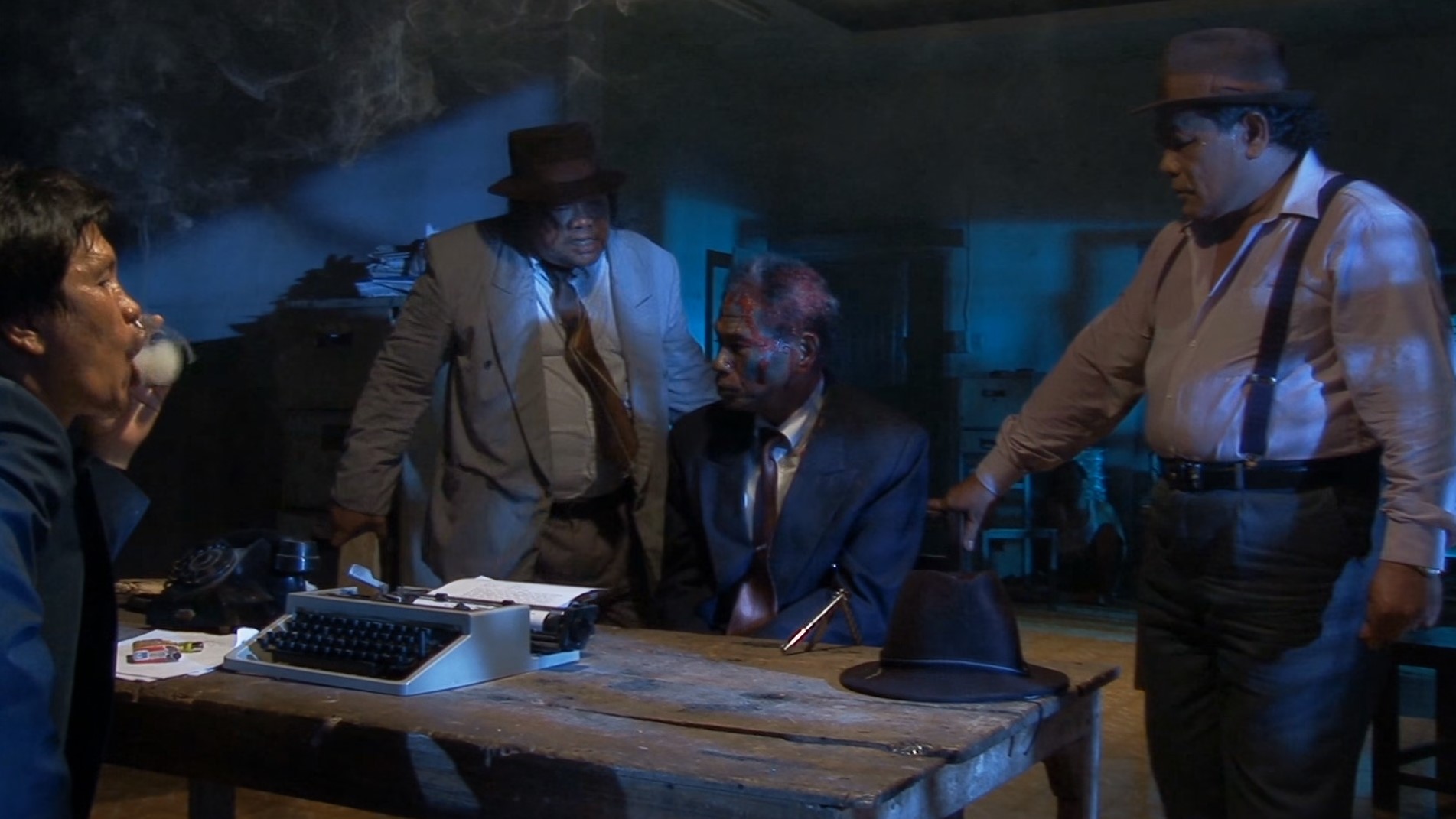

The Act of Killing, unlike the traditional documentary format, tells the story from the perspective of the perpetrator rather than the victim. This was a necessary choice given the unwillingness of the victims to speak out, but I think it makes for a stronger, bolder, and better documentary. The director’s choice to ask the mass murderers who killed so many people in Indonesia’s tragic history to re-enact their actions and make a movie about them effectively conveys the horrific reality of the past to the audience. Through the dramatic form of their re-enactments and reconstructions, the director asks the question, “What do you think about what you have done?” and invites them to answer it for themselves.

They show no shame or remorse for their past actions, even in the process of making the film, but rather present themselves as strong and brutal, trying to instill fear as if killing is something they are capable of. They also have the audacity to claim they are the victors, claiming that they don’t have to hide it at all because the statute of limitations has run out. This isn’t just about the individuals, but about how much they have become socially accepted and justified.

In particular, there’s a 43-minute interview where they’re asked what they think of other movies that deal with the same subject matter. They complain that they’ve been demonized in those films, and they say that their films should show the brutality as it is, but claim that their actions were justified. At this point, I was reminded of how powerful the artistic medium of film is in shaping public perception, and horrified at what it can do when used with the wrong intentions. It made me reflect on how many mediums have reached out to the public with such bad intentions, and how often we are drawn to them. It made me question what I was doing as an artist.

In the middle of the movie, there is a scene that is aired on Indonesian national television, and it marks an important turning point in the movie. Up until this point, the film had been centered on the perpetrators’ private conversations or re-enactments, but here they are in public, openly discussing their past actions. At this point, I felt like I was letting go of everything. Knowing the power of the medium of broadcasting to influence the public, I was shocked to see them publicly justify their actions. I think this was Oppenheimer’s intention in inserting this scene in the middle of the movie, as it was the most shocking moment of the movie and, for me, the peak of my anger.

The first half of the movie is filled with the brutality of the perpetrators and the triumphant feeling they get. But in the second half, as Anwar Congo struggles with the process of making the film, telling himself he can’t do it anymore, watching the footage back and realizing his cruelty, and breaking down in tears, it’s a deeply affecting moment. He goes from smiling innocently and reenacting the events of the day to feeling nauseated and tormented. This dramatic reversal reveals that they are human after all, and evokes complex emotions in the audience. This scene was bound to elicit a long, long sigh.

But now, as I watch them shed tears of penance, I’m confused as to what emotion I should feel: they’re still living their lives normally, perhaps even luxuriously. They are not demons, they are not psychopaths. Their evil acts are not the result of their own evil personalities, but rather the product of their societal backgrounds and circumstances. In the end, The Act of Killing is not a movie about exceptional, innately evil people in history, but about the conditions and systemic violence that make such acts possible.

It’s a film that nakedly exposes the faces of power and criticizes the structural problems of the society we live in. Oppenheimer uses a very clever way of directing to convey this message. Long after the fall of Suharto’s regime, the perpetrators of the massacre are still being heroized rather than condemned, and the organization that carried out the massacre has evolved into a private army and is now a thriving far-right activist organization. Under these circumstances, the director shifts the focus to the perpetrators, not the victims, and attempts to report closely on the massacre.

The film shows how humans who do not consider themselves evil realize their wrongdoing through the process of re-enacting the massacre, and then justify it again. It’s an incredibly bold idea. Oppenheimer ultimately succeeds in capturing the Indonesian tragedy from the perspective of the victims. As the film is told from the point of view of the perpetrators, Oppenheimer almost excludes his own subjectivity and tells the story from the point of view of an observer. One of the important features of documentaries, the use of footage or music, is completely avoided, and the role of footage is fulfilled by the footage of them making the movie.

The film takes the form of an explanatory documentary in that it directly addresses real-world issues. However, unlike traditional expository documentaries, the film is not didactic or authoritarian in nature, so in some ways it can be considered a participatory documentary. The story is told solely through the voices of the perpetrators themselves, with the director’s voice removed from the process of eliciting their past behavior through interviews. This approach can feel very ambiguous, but I think this is what the director intended.

In particular, I found the intercut scenes of the perpetrators’ daily lives puzzling. Even in the midst of their normal routines, they seem to reveal their cruelty. For example, roughly brushing their teeth or gagging, removing their dentures and checking them with pliers, etc. are routines that anyone can do, but their behavior in the eyes of others is clearly repulsive. The director seems to be trying to instill a sense of rejection in the audience through these scenes.

In the middle of the movie, we are shown taxidermied animals, which are edited back to back with the murder scenes, making the taxidermied animals look like people. In this way, the director uses editing and directing to reveal his point of view and convey the intention of the movie to the audience without using direct visuals. This is very original and makes the message the director wants to convey even stronger.

The Act of Killing is not just a documentary. It is an indictment of the violence, massacres, and aftermath that occurred during the struggle for political democratization. Indonesia’s past is not so different from Korea’s. Korea also went through a pro-democracy struggle, and many intellectuals and trade unionists were rounded up by the Communist Party, tortured, and massacred. I got goosebumps when I realized how similar Indonesia was to my own society. If Korea had not gone through the democratic uprising, our current society might not be different from Indonesia.

The movie also reminds us of how our society has changed and that we still have a lot of historical issues that need to be resolved. If we don’t properly liquidate the wrongs of the past, they will continue to hold us back and hinder our progress. The movie shows how deformed a society can become when the powerful monopolize power and dominate it. Constant checks on power and the courage to act on our beliefs in social justice are the only alternatives to prevent tragedy.