Michael Moore’s films critique the structural contradictions of American capitalism, highlighting issues of poverty and labor. Rather than denying capitalism itself, he argues that we should use democracy to correct its negative aspects and move toward a better capitalism.

I have a favorite filmmaker. He was very influential in changing the healthcare system in the United States. Michael Moore is best known as the director of the movie SICKO. I watched another of his films, Capitalism: A Love Story. This movie was released in 2009. A long time ago, this movie sparked the “Occupy Wall Street” movement. In this movie, Michael Moore criticizes capitalism, which has become an article of faith in American society. In the movie, he uses various examples and evidence to argue that individual poverty is not the result of laziness or lack of ability, but rather of structural social problems.

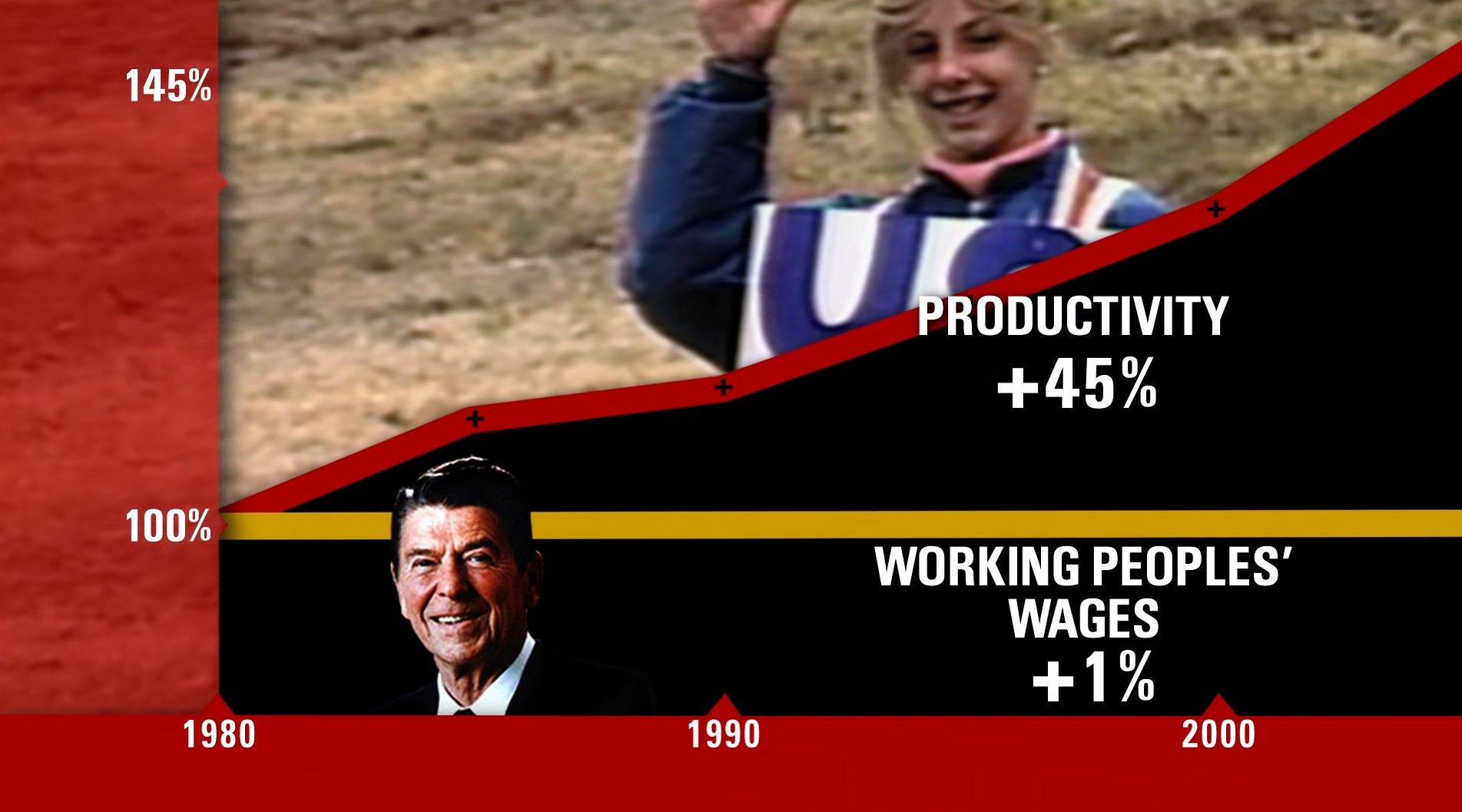

The praise and admiration for American capitalism has been a force that has sustained the country, but Michael Moore questions its roots. Was it really the adoption of capitalism that made America’s growth possible? America’s growth was largely a function of the times. World War II destroyed the industrial base of Germany and Japan. In its wake, the United States experienced explosive growth in exports and domestic demand in most industries, including manufacturing. This helped fuel the growth of the American middle class. But growth has its limits, and with the reemergence of Japan and Germany and the rise of the developing world, the United States entered a recession. Ronald Reagan took office. Reagan’s revolutionary tax policies and economic plans are credited with revitalizing the US economy. In fact, under Reagan, the U.S. became the center of the world economy. But behind the scenes, his methods of revitalizing the economy put the U.S. economy and finance at risk in the long run. He laid off many American workers and asked those who remained to do more work at the same wages as before. Companies’ labor costs went down and productivity went up, benefiting them and their shareholders. However, the income tax rates for the wealthy were reduced. So, who did the gains go to? On the one hand, people suffer from years of unemployment because they can’t find a job, and on the other hand, workers are tied to their companies day and night with work that is pushed on them. In the name of labor flexibility, there are fewer and fewer full-time jobs and more and more part-time jobs, and the power of individuals to stand up to corporations and the larger social structure has become increasingly tenuous. Slowly, the groundwork was being laid for a league of their own.

The gap between the rich and the poor widens, and the middle class begins to collapse. The gap between the rich and the poor widens, and the middle class begins to decline. The rising household debt was an opportunity for the U.S. stock market and its executives, who lent up to 90% against homes and duped citizens with complex derivatives. Corporations bought expensive life insurance policies in their employees’ names without their knowledge, and collected huge payouts when the employees died, with their families never knowing about it, and with no benefit to the families who really needed it. This seemingly thriving American society began to unravel when the subprime mortgage crisis erupted. Mortgage lenders and investment banks went bankrupt, and people were left homeless and on the street.

In the midst of this economic crisis, President George W. Bush appeals for the passage of a $700 billion budget. The plan was to bail out the financial sector with taxpayer money. Meanwhile, Wall Street had been steadily increasing its influence on the government. Starting with Donald Regan, the CEO of Merrill Lynch, and continuing with Robert Rubin and Larry Summers, the CEOs of Goldman Sachs, Wall Street has been able to get their way as Treasury secretaries. The government lost its role of overseeing and controlling the financial sector, and Wall Street took the government into its own hands by pouring money into the government. In the end, the budget was passed, and the taxes of hard-working Americans were used to pay for Wall Street’s payoffs.

Angry citizens take to the streets, chanting “Occupy Wall Street!” On one side, laid-off workers protest against their employers. Their protest seems to show that there is still hope for America. Citizens bring food to the laid-off workers, who have been isolated, and police protect them. It’s heartwarming to see the American public support the laid-off workers. In the end, the laid-off workers’ demands are accepted by the company.

Michael Moore knows how to get his point across effectively; his films have the power to persuade, move, and inspire people to action. However, he is limited by the fact that he only presents examples that support his argument. Collecting and editing only the material you think you need and presenting it as if it’s all there is is a one-sided interpretation of a phenomenon, and that’s why his arguments are so extreme. This approach appeals to people, and it has the advantage of making them aware of the problem and communicating it effectively. However, it’s not the right way to solve a problem if you’re blindly supporting one side or the other. I don’t think it’s good to boil it down to a 1% vs. 99% debate. The voice of the 99% will get quieter and quieter as the 98% and 97% get louder and louder. In the end, the underlying problem is not solved. It’s not about confrontation and choosing sides, it’s about the right and the left coming together and finding a consensus. In that sense, I think we need to study the greedy 1% in the movie, rather than just focusing on them. I wonder why they made the choices they did in their lives, their culture, their way of life. I want to understand them, to find the cracks in their culture and make them self-reflective.

I hope to find humanity in them because I think we are social animals, or at least we used to be, who can live together. In fact, the word “humanity” has so many meanings that it is impossible to define one. We know that the good humanity of a primitive tribe living in an incredibly selfless way, or the brutality of killing one’s own kind, as evidenced by the countless wars and genocides throughout human history, is all part of humanity. We have looked to other cultures for clues to the solutions we need. We need to look deeper and from different perspectives to find solutions to the problems facing America and all of us.

Michael Moore’s films are fascinating because they show our already familiar way of life in an unfamiliar frame. It gives us a new perspective on the big picture that we have lost in the daily grind. His films are not only a critique of his own society, but also a mirror that allows other societies to see themselves in the light of their own society. In addition, his films, which are critically analyzed from the point of view of the relative underdog, are able to shatter the illusion of capitalism that has been imprinted by the vested interests.

Michael Moore does not deny capitalism. He advocates for the restoration of proper capitalism through democracy. However, I hope that we can move away from the idea that humans are only interested in economic gain. As long as we keep this value, there will always be poverty and greed. The solution lies in finding values other than economics. It’s not about standing up to the 1% and asking them to make enough money for the rest of us. It’s about changing our standards of humanity and finding the humanity we’ve lost.