Emerging from the limitations of classical mechanics, quantum theory led to a revolution in modern physics. The Copenhagen School’s interpretation of quantum theory, which emphasizes a probabilistic interpretation of the wave function and the role of the observer, is the mainstream interpretation of quantum theory. However, this interpretation has sparked a long debate and is still subject to question and criticism.

“Quantum theory” is a physics theory that describes the microscopic world. A microscopic quantum world is one that is roughly one nanometer in size. Until the 19th century, classical mechanics, represented by Newtonian mechanics, was considered the truth of physics. However, with the development of quantum theory, classical mechanics underwent a major change.

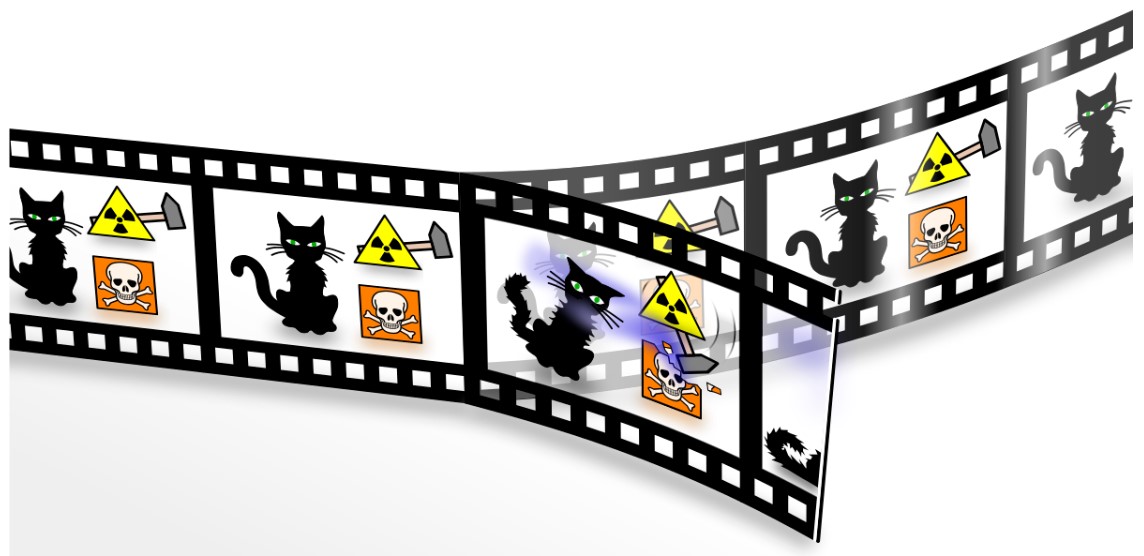

Quantum theory, which began in 1900, and relativity, which began in 1905, have had a profound impact not only on science, but also on human culture and society. In classical mechanics, represented by Newtonian mechanics, “matter” is the center of the world. It has mass, it has position, and it has kinetic or potential energy. The role and purpose of classical mechanics is to calculate the motion of matter to predict the future and verify it through experiments. In the material worldview, matter can exist alone. Matter is “real” even if someone observes or experiments with it. This theory is called determinism, or realism. Einstein and Schrödinger are two of the most prominent people who believed in and studied determinism. Schrödinger conducted his famous thought experiment called Schrödinger’s Cat in 1935.

(Source – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Schroedingers_cat_film_copenhagen.svg)

This thought experiment involves an alpha male and a cat. The cat is placed in a box that is completely closed off from the outside world. The box is connected to a canister of poisonous gas. The poison gas cannot enter the box because it is blocked by a valve, and the canister of poison gas is also blocked from the outside world and cannot see if the valve is open. The valve is connected to a mechanical device that detects radioactivity. When the radium decays, which is set to alpha decay with a 50% chance per unit time, the mechanism detects the alpha particles released in the process and opens the valve. If the valve opens, the cat will inhale the poisonous gas and die. Then, after that unit of time, the cat has a 50% chance of being alive or dead. In this thought experiment, a determinist would think that after a unit of time, the cat would be either dead or alive without having to check. Schrödinger argued that there is no such thing as a cat that is both dead and alive. He believed that quantum mechanics is incomplete and unrealistic.

The Copenhagen School, which is the opposite of the determinism and realism described above, holds that there are cats that are both dead and alive. The Copenhagen School includes Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg, and others. In a nutshell, the Copenhagen School’s interpretation is that a wavefunction is represented by a stochastic superposition of several states before it is measured, and when an observer makes an observation, a “wavefunction collapse” occurs, crystallizing the wavefunction from the superposition into a single state. In classical mechanics, physical objects were thought to exist as either particles or waves, while Bohr of the Copenhagen School thought that physical objects could exist in two states simultaneously: particles and waves. Heisenberg then proposed the principle of indeterminacy, which states that the position and momentum of a particle cannot be measured accurately at the same time. The Copenhagen School interpreted Schrödinger’s cat as a dead cat and a living cat simultaneously while the box is closed, but the moment the box is opened to check the cat’s state, the cat must be determined to be in one of the two states. In other words, the core of the Copenhagen interpretation is that the value of a physical quantity has meaning after the act of measurement.

Here I would like to ask the question: are not the observer and the act of measurement itself still described in the classical way of the world? Under the laws of quantum mechanics, the observer, the instrument, and the act of measurement must obey the laws of quantum mechanics, which apply equally to all other objects in the universe. However, in the Copenhagen interpretation, the rules are expressed as wave functions that follow the deterministic progression we discussed earlier. It is true that the probabilistic rules of the Copenhagen interpretation work well in practice. However, this does not mean that it ultimately explains everything about quantum theory. I think of it this way. I think that the physical state of a substance can be determined independently of measurement, or it can be determined by interaction with the measurement process, as the Copenhagen interpretation claims. However, I don’t agree that the latter is 100% true, because our observations and measurements may not be perfect enough to reveal all the properties of an object. According to the Copenhagen interpretation, some physical quantities do not have fixed values, but are only determined through observation. Take Major League Baseball for example. Suppose a pitcher named Otani of the Los Angeles Dodgers throws a ball to a catcher, and the speed of the ball is measured by the team and broadcasters. The MLB team measured the velocity at 163 km/h, while the NHK broadcaster measured it at 161 km/h. Does this mean that the ball actually had a velocity of 163 km/h and 161 km/h? I don’t think so. I believe that the difference in measurement results is due to the fact that the measuring instruments are not 100% perfect. For the Copenhagen interpretation to be convincing, they would have to show that their observations are within the laws of quantum mechanics. It’s not enough to simply say that it’s an experiment. This is why the Copenhagen interpretation is still not 100% accepted in the scientific community.

Human perception is imperfect. Even the act of making an observation can be subjective, as it goes through our brain. For this reason, the act of observation in the Copenhagen interpretation needs to be redefined. If a third party, who may not actually exist, but who is invisible to us and has an omniscient view of the world we live in, were to observe Schrödinger’s cat thought experiment, would he be able to know the state of the cat in the box? Isn’t it just that our act of observation is an imperfect act, and the outcome appears as a wave function of probability?

I have argued against the Copenhagen interpretation, which is currently recognized as mainstream within the quantum theory community. If we can prove this interpretation wrong, it will be a major contribution to the history of science. However, I think it’s a good idea to think about this interpretation at least once, rather than accepting it at face value. The quantum world is still unexplored, but I believe that one day we will find out what it is.